Class - 1

Sources for the history of Modern India:

The records of the East India Company provide a detailed account of trading conditions during the period 1600-1857. When the British crown took over the administration, it also kept a large variety and volume of official records.

- These records help historians to trace every important development stage-by-stage and follow the processes of decision-making and the psychology of the policy-makers.

- The records of the other European East India companies (the Portuguese, Dutch and French) are also useful for constructing the history of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The National Archives of India, located in New Delhi, contains most of the archives of the Government of India. These provide authentic and reliable source materials on varied aspects of modern Indian history.

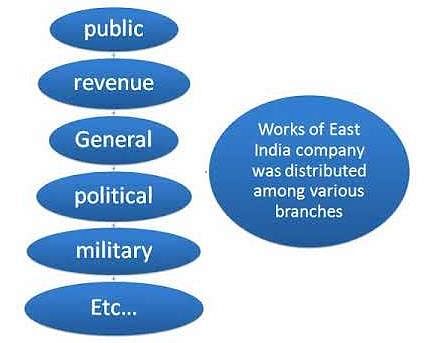

- The records with the National Archives come under various groups, representing different branches of the secretariat at different stages of its development. This happened as the work of the East India Company was distributed among various branches—public or general, revenue, political, military, secret, commercial, judicial, education, etc.—and a separate set of records was kept for each of these branches or departments.

- With the appointment of James Rennell as the first Surveyor-General of Bengal in 1767, the Survey of India began to scientifically map the unknown regions of the country and its bordering lands.

The source material in the state archives comprises the records of:

(i) The former British Indian provinces.

(ii) The erstwhile princely states which were incorporated in the Indian Union after 1947

(iii) The foreign administrations other than those of the British.

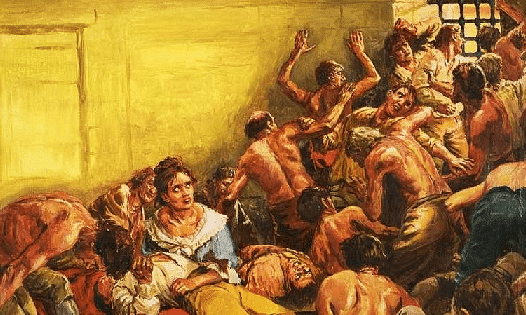

- The early records of Fort Williams (Bengal Presidency) were lost during the sack of Calcutta in 1756, but the archives of the Bengal presidency after the British victory at Plassey have survived more or less in a complete series, which are partly available in the National Archives of India and partly in the State Archives of West Bengal.

- The records of the Madras Presidency begin from AD 1670 and include records of the Governor and Council of Fort St. George.

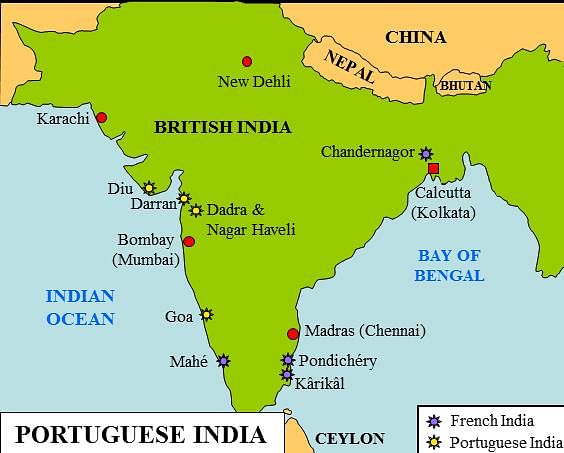

- The archives related to the Portuguese preserved in Goa, mainly belonging to the period from 1700 to 1900, are valuable for the history of Portuguese possessions in India.

- The Dutch records of Cochin and Malabar are in the Madras Record Office and those of Chinsura in the state archives of West Bengal.

- The French archives of Chandernagore and Pondicherry (now Puducherry) were taken to Paris by the French authorities before they relinquished these settlements.

- The remaining Danish records, mainly relating to Tranquebar (1777-1845), are now housed in the Madras Record Office.

- Housed in the Madras Record Office, the archives of the Mayor’s Court at Fort St. George, beginning from AD 1689, are the earliest available judicial archives.

- The pre-Plassey records of the Mayor's Court at Fort Williams have been lost, but those for the years 1757-73 are kept in the record room of the Calcutta High Court, along with the archives of the Supreme Court of Bengal 1774-1861.

- The most significant archival publications are the Parliamentary Papers which include many excerpts from the records of the East India Company and the Government of India under the Crown.

- Private archives comprise papers and documents of individuals and families of note, who played a significant role in the development of modern India.

- In England, the India Office Records, London and the records kept in the British Museum are very valuable.

The India Office Records possesses various important documents:

The minutes of the Courts of Directors and the General Court of the East India Company and various committees constituted from time to time, the minutes and correspondence of the Board of Control or the Board of Commissioners for the Affairs of India, and the records of the Secretary of State and the India Council. - The British Museum possesses collections of papers of British viceroys, secretaries of states and other high ranked civil and military officials who were posted in India. The archives of the missionary societies, for instance, of the Church Missionary Society of London, provide insight into the educational and social development in pre-independent India.

- Many travellers, traders, missionaries and civil servants who came to India, have left accounts of their experiences and their impressions of various parts of India. An important group among these writers was that of the missionaries who wrote to encourage their respective societies to send more missionaries to India for the purpose of evangelising its inhabitants.

- In this genre, Bishop Heber’s Journal and Abbe Dubois's Hindu Manners and Customs, provide useful information on the socio-economic life of India during the period of decline of the Indian powers and the rise of the British.

- Newspapers and journals of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, published in English as well as in the different vernacular languages, form an important and authentic source of information for the construction of the history of modern India. The first attempts to publish newspapers in India were made by the disgruntled employees of the English East India Company who sought to expose the malpractices of private trade.

- In 1780, James Augustus Hickey published the first newspaper in India entitled The Bengal Gazette or Calcutta General Advertiser. Hickey's press was seized within two years, owing to his outspoken criticism of government officials. Afterwards, many publications appeared such as The Calcutta Gazette (1784), The Madras Courier (1788) and The Bombay Herald (1789).

- From the second half of the 19th century, some of their publications were: The Hindu and Swadesamitran under the editorship of G. Subramaniya Iyer, Kesari and Mahratta under Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bengalee under Surendranath Banerjea.

- Oral history refers to the construction of history with the help of non-written sources, for instance, personal reminiscence.

- The most significant outcome of the Indo-European contact was the novel which emerged in the latter half of the 19th century. The first important writer of that period was the famous Bengali novelist, Bankim Chandra Chatterji (1838 - 94). His novels are mostly historical, the best known among them being Anand Math (1882), especially for its powerful lyric 'Vandemataranr and depiction of the Sanyasi Revolt (1760s).

- G.V. Krishna Raos Kilubommalu (The Puppets, 1956) in Telugu was concerned with the moral aspects and behavior of the rural people.

- Vaikom Muhammad Basheer (19-10-1994) was one of the eminent writers in Malayalam whose famous novel Balyakala Sakhi (The Childhood Friends, 1944) was a tragic tale of love.

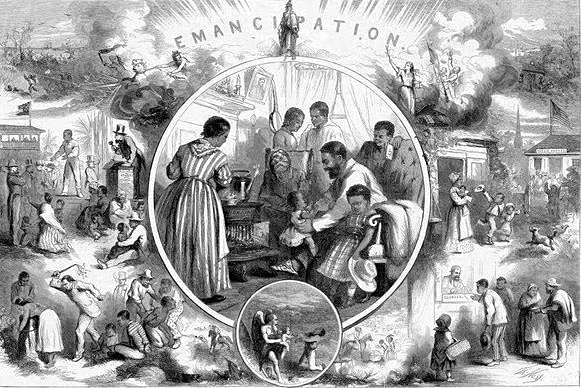

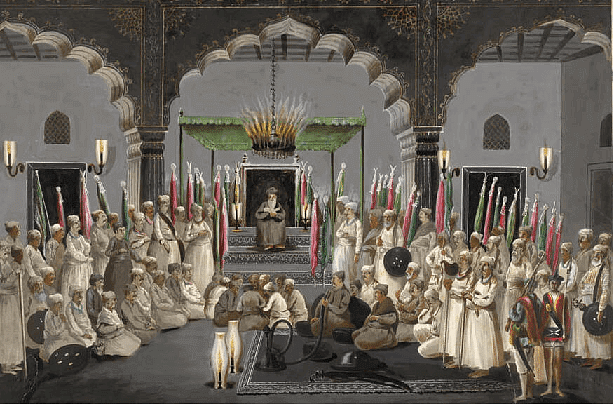

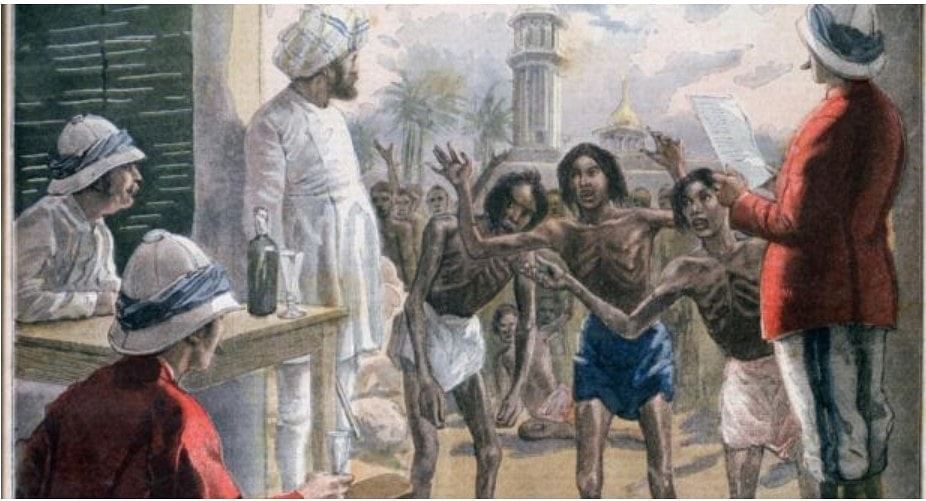

- Some information on the socio-economic, political and cultural life during the colonial period can be obtained from the paintings of that period.

- The Company Paintings, also referred as ‘Patna Kalam' emerged under the patronage of the East India Company. They picturise the people and scenes as they existed at the time. Trades, festivals, dances and the attire of people were visible in these works.

- Another painting of this period, In Memoriam by Joseph Noel Paton, recorded in painting two years of the revolt of 1857. One can see English women and children huddled in a circle, looking helpless and innocent, seemingly waiting for the inevitable—dishonour, violence and death.

- The establishment of the East India Company in 1600 and its transformation into a ruling body from a trading one in 1765 had little immediate impact on Indian polity and governance.

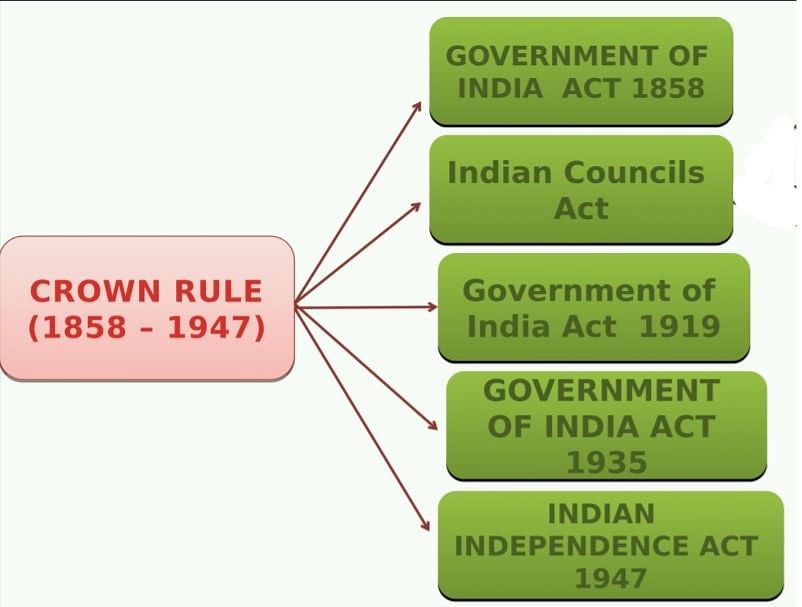

- But the period between 1773 and 1858 under the Company rule, and then under the British Crown till 1947, witnessed a plethora of constitutional and administrative changes.

Coat of arms of the East India Company

Coat of arms of the East India Company - The nature and objective of these changes were to serve the British imperial ideology but unintentionally they introduced elements of the modern State into India’s political and administrative system.

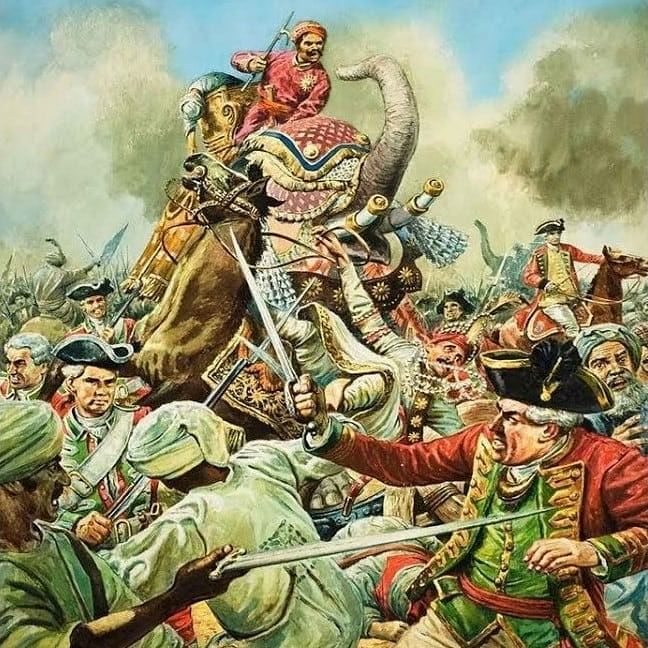

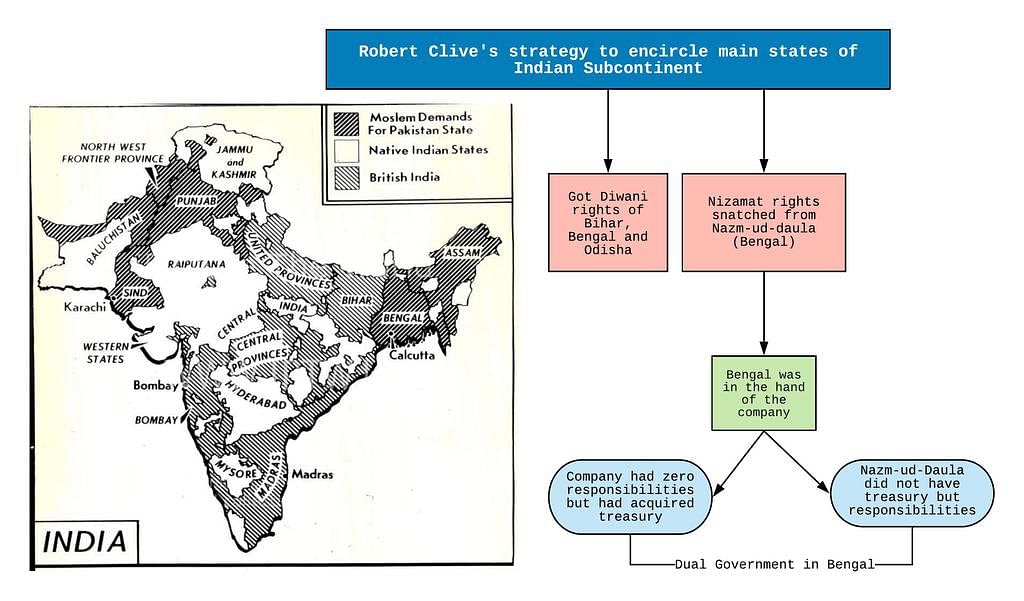

- After the Battle of Buxar (1764), the East India Company got the Diwani (right to collect revenue) of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- 1767- The first intervention in Indian affairs by the British government came in 1767.

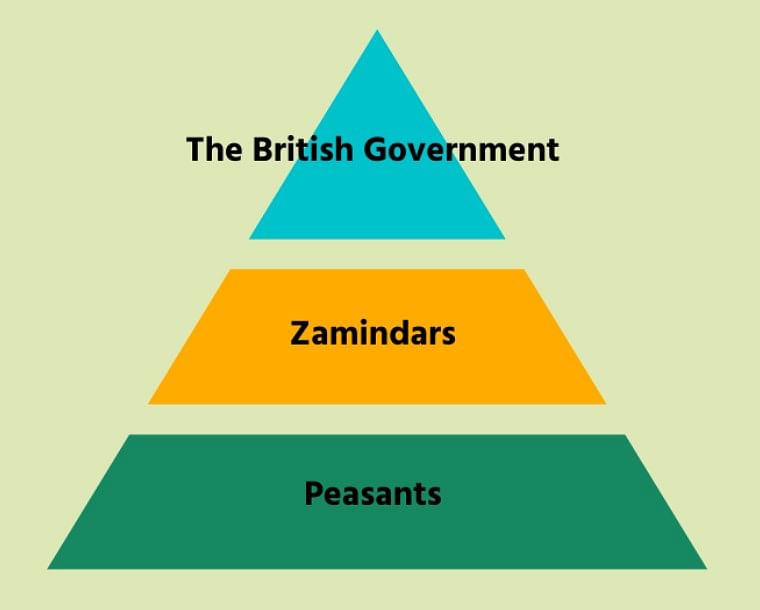

- 1765-72- This period was characterized by

(i) Rampant corruption among servants of the Company who made full use of private trading to enrich themselves;

(ii) Excessive revenue collection and oppression of peasantry;

(iii) Company’s bankruptcy, while the servants were flourishing.

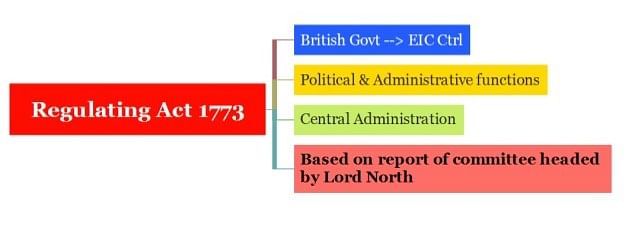

The Regulating Act of 1773 (formally, the East India Company Act 1772) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain intended to overhaul the management of the East India Company's rule in India.

- British government’s involvement in Indian affairs in the effort to control and regulate the functioning of the East India Company. It recognized that the Company’s role in India extended beyond mere trade to administrative and political fields, and introduced the element of centralized administration.

- Directors of the Company were required to submit all correspondence regarding revenue affairs and civil and military administration to the government.

- In Bengal, the administration was to be carried out by the governor-general and a council consisting of 4 members, representing the civil and military government. They were required to function according to the majority rule.

- A Supreme Court of judicature was to be established in Bengal with original and appellate jurisdictions where all subjects could seek redressal. In practice, however, the Supreme Court had a debatable jurisdiction vis-a-vis the council which created various problems.

- Governor-general could exercise some powers over Bombay and Madras—again, a vague provision which created many problems.

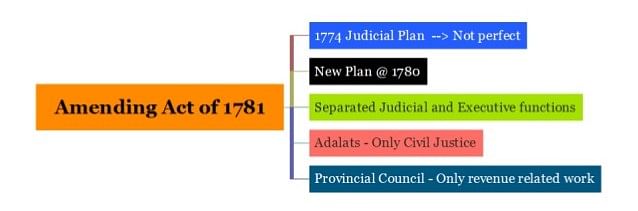

Amendments (1781)

(ii) Servants of the government were immune if they did anything while discharging their duties.

(iii) Social and religious usages of the subjects were to be honoured.

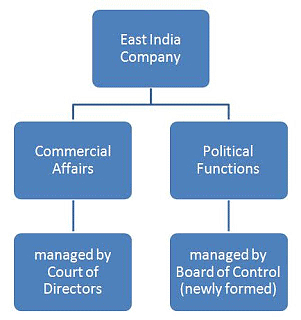

The Pitt's India Act of 1784, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain intended to address the shortcomings of the Regulating Act of 1773 by bringing the East India Company's rule in India under the control of the British Government.

- The company became a subordinate department of the State. The Company’s territories in India were termed British possessions’.

- A Board of Control consisting of the chancellor of the exchequer, a secretary of state and four members of the Privy Council (to be appointed by the Crown) were to exercise control over the Company’s civil, military, and revenue affairs. All dispatches were to be approved by the board. Thus a dual system of control was set up.

- In India, the governor-general was to have a council of three (including the commander-in-chief), and the presidencies of Bombay and Madras were made subordinate to the governor-general.

- A general prohibition was placed on aggressive wars and treaties (breached often).

In 1786 Pitt brought another bill in the Parliament relating to India in a bid to prevail upon Cornwallis to accept the Governor Generalship of India.

- Cornwallis wanted to have the powers of both the governor-general and the commander-in-chief. The new Act conceded this demand and also gave him power.

- Cornwallis was allowed to override the council’s decision if he owned the responsibility for the decision. Later, this provision was extended to all the governors-general.

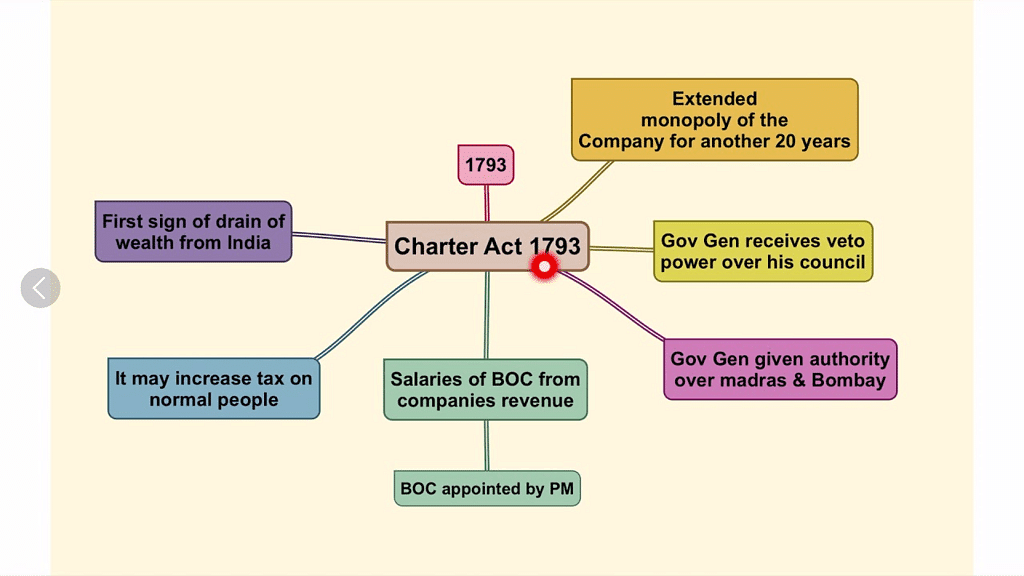

The Charter Act of 1793, also known as the East India Company Act 1793 was passed in the British Parliament in which the company charter was renewed.

- The Act renewed the Company’s commercial privileges for the next 20 years.

- The Company, after paying the necessary expenses, interest, dividends, salaries, etc., from the Indian revenues, was to pay 5 lakh pounds annually to the British government.

- The royal approval was mandated for the appointment of the governor-general, the governors, and the commander-in-chief.

- Senior officials of the Company were debarred from leaving India without permission—doing so was treated as a resignation.

- The Company was empowered to give licenses to individuals as well as the Company’s employees to trade in India. The licenses, known as 'privilege’ or 'country trade', paved the way for shipments of opium to China.

- The revenue administration was separated from the judiciary functions and this led to the disappearance of the Maal Adalats.

- The Home Government members were to be paid out of Indian revenues which continued up to 1919.

The Charter Act of 1813 passed by the British Parliament renewed the East India Company’s charter for another 20 years.This act is important in that it defined for the first time the constitutional position of British Indian territories.

- The Company’s monopoly over trade in India ended, but the Company retained the trade with China and the trade-in tea.

- The Company’s shareholders were given a 10.5 percent dividend on the revenue of India. The Company was to retain the possession of territories and the revenue for 20 years more, without prejudice to the sovereignty of the Crown.

- Powers of the Board of Control were further enlarged.

- A sum of one lakh rupees was to be set aside for the revival, promotion, and encouragement of literature, learning, and science among the natives of India, every year.

- The regulations made by the Councils of Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta were now required to be laid before the British Parliament. The constitutional position of the British territories in India was thus explicitly defined for the first time.

- Separate accounts were to be kept regarding commercial transactions and territorial revenues. The power of superintendence and direction of the Board of Control was not only defined but also enlarged considerably.

- Christian missionaries were also permitted to come to India and preach their religion.

The lease of 20 years to the Company was further extended in the Charter Act of 1833. Territories of India were to be governed in the name of the Crown.

- The company’s monopoly over trade with China and in tea also ended.

- All restrictions on European immigration and the acquisition of property in India were lifted.

- In India, a financial, legislative, and administrative centralization of the government was envisaged:

(i) Governor-general was given the power to superintend, control, and direct all civil and military affairs of the Company.

(ii) Bengal, Madras, Bombay, and all other territories were placed under complete control of the governor-general.

(iii) All revenues were to be raised under the authority of the governor-general who would have complete control over the expenditure too.

(iv) Governments of Madras and Bombay were drastically deprived of their legislative powers and left with a right of proposing to the governor-general the projects of law which they thought to be expedient. - A law member was added to the governor-general’s council for professional advice on lawmaking. vi. Indian laws were to be codified and consolidated. vii. No Indian citizen was to be denied employment under the Company on the basis of religion, color, birth, descent, etc

- The administration was urged to take steps to ameliorate the conditions of slaves and to ultimately abolish slavery. (Slavery was abolished in 1843.)

The Charter Act 1853 was passed in the British Parliament to renew the East India Company’s charter. Unlike the previous charter acts of 1793, 1813 and 1833 which renewed the charter for 20 years; this act did not mention the time period for which the company charter was being renewed.

- The company was to continue possession of territories unless the Parliament provided otherwise.

- The strength of the Court of Directors was reduced to 18.

- The company’s patronage over the services was dissolved—the services were now thrown open to a competitive examination.

- Law member became the full member of the governor-general’s executive council.

- separation of the executive and legislative functions of the Government of British India progressed with the inclusion of six additional members for legislative purposes

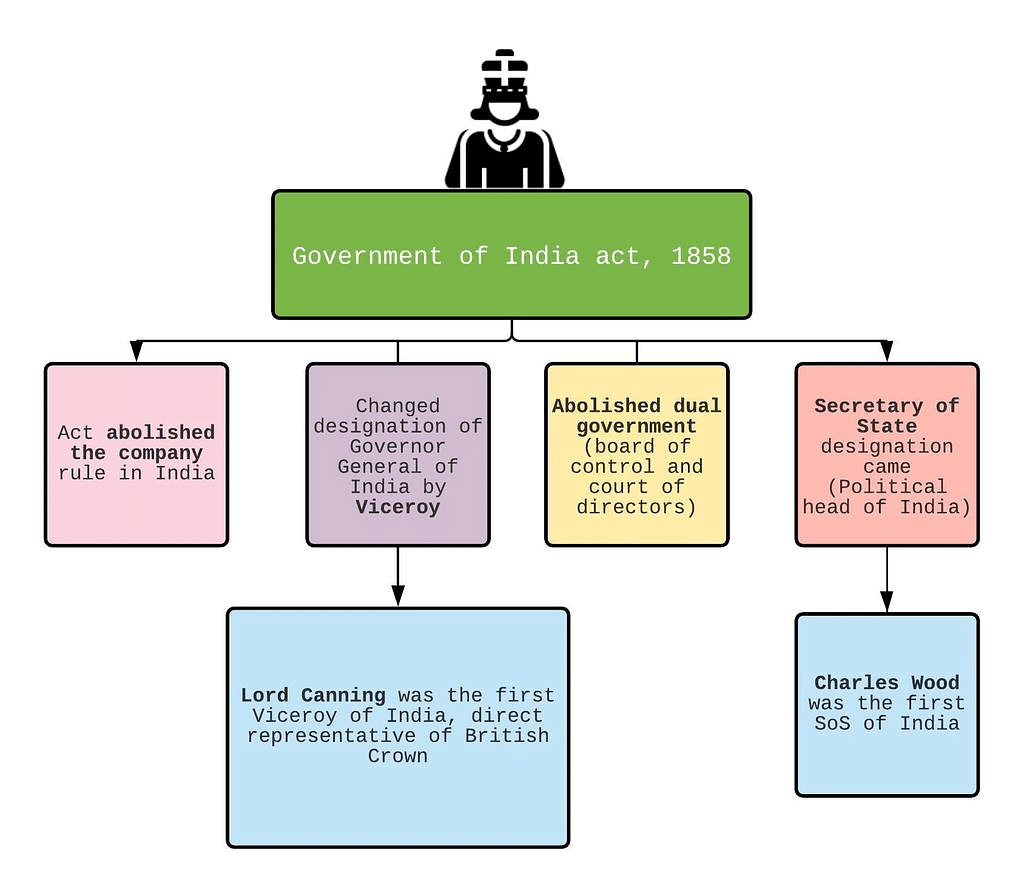

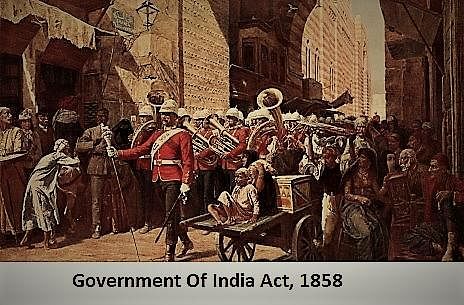

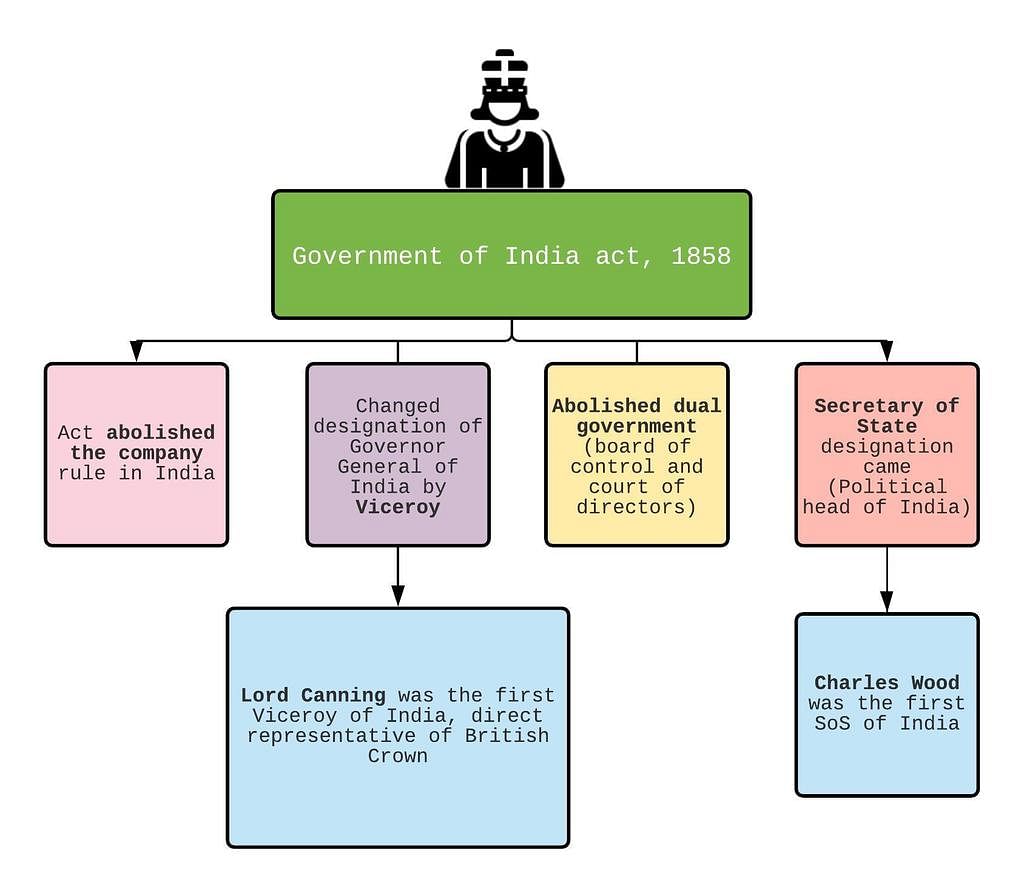

The Government of India Act 1858 was an Act of the British parliament that transferred the government and territories of the East India Company to the British Crown.

- The company’s rule over British territories in India came to an end and it was passed directly to the British government.

- India was to be governed by and in the name of the Crown through a secretary of state and a council of 15. The initiative and the final decision was to be with the secretary of state and the council was to be just advisory in nature.

- Governor-general became the viceroy

The Indian Councils Act 1861 was an act of the British Parliament that made significant changes in the Governor-General’s Council.

- The 1861 Act marked an advance in that the principle of representatives of nonofficials in legislative bodies became accepted; laws were to be made after due deliberation, and as pieces of legislation they could be changed only by the same deliberative process.

- The portfolio system introduced by Lord Canning laid the foundations of cabinet government in India, each branch of the administration having its official head and spokesman in the government, who was responsible for its administration.

- The Act by vesting legislative powers in the Governments of Bombay and Madras and by making provision for the institution of similar legislative councils in other provinces laid the foundations of legislative devolution.

The Indian Councils Act 1892 was an act of the British Parliament that increased the size of the legislative councils in India.

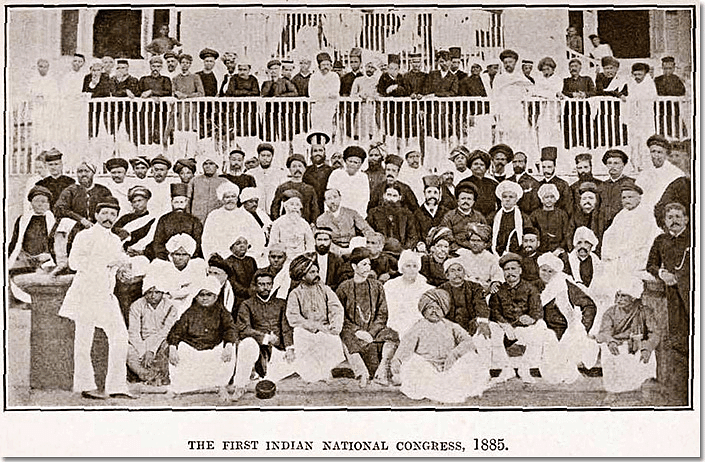

- In 1885, the Indian National Congress was founded. Congress saw the reform of the councils as the “'root of all other reforms ’. It was in response to the Congress's demand that the legislative councils be expanded that the number of non-official members was increased both in the central (Imperial) and provincial legislative councils by the Indian Councils Act, 1892.

- Legislative Council of the Governor-General was enlarged.

- Universities, district boards, municipalities, zamindars, trade bodies, and chambers of commerce were empowered to recommend members to the provincial councils.

- Thus was introduced the principle of representation.

- Though the term election' was firmly avoided in the Act, an element of the indirect election was accepted in the selection of some of the non-official members.

- Members of the legislatures were now entitled to express their views upon financial statements which were henceforth to be made on the floor of the legislatures.

- Could also put questions within certain limits to the executive on matters of public interest after giving six days’ notice.

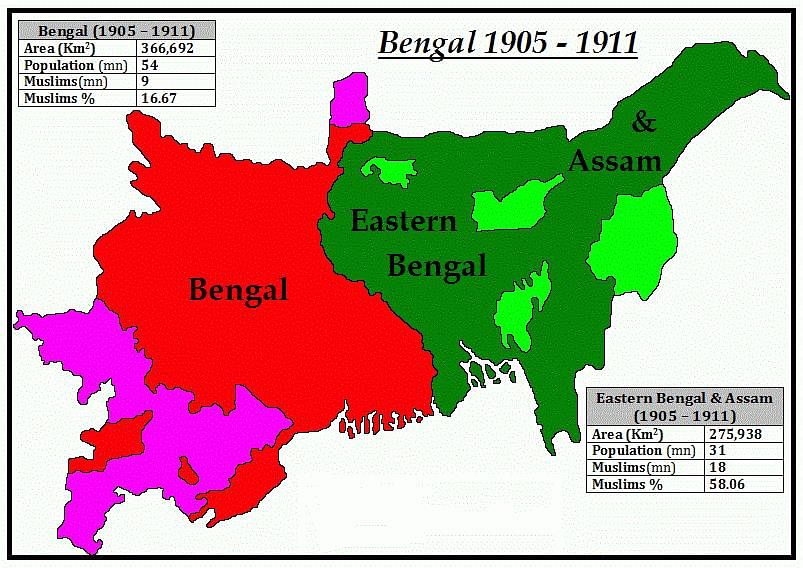

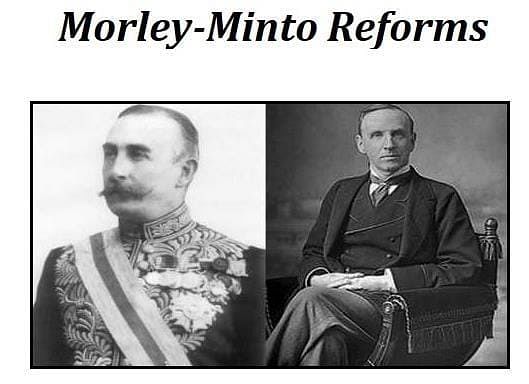

The Indian Councils Act 1909 was an act of the British Parliament that introduced a few reforms in the legislative councils and increased the involvement of Indians (limited) in the governance of British India.

- Popularly known as the Morley-Minto Reforms, the Act made the first attempt to bring in a representative and popular element in the governance of the country.

- The strength of the Imperial Legislative Council was increased.

- With regard to the central government, an Indian member was taken for the first time in the Executive Council of the Governor-General

- Members of the Provincial Executive Council were increased.

- Powers of the legislative councils, both central and provincial, were increased.

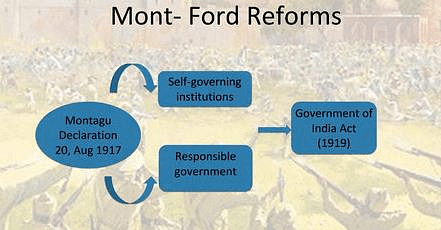

The Government of India Act 1919 was an act of the British Parliament that sought to increase the participation of Indians in the administration of their country.

- This Act was based on what is popularly known as the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms.

- Under the 1919 Act, the Indian Legislative Council at the Centre was replaced by a bicameral system consisting of a Council of State (Upper House) and a Legislative Assembly (Lower House). Each house was to have a majority of members who were directly elected. So, the direct election was introduced, though the franchise was much restricted being based on qualifications of property, tax, or education.

- The principle of communal representation was extended with separate electorates for Sikhs, Christians, and Anglo-Indians, besides Muslims.

- The act introduced dyarchy in the provinces, which indeed was a substantial step towards the transfer of power to the Indian people.

- The provincial legislature was to consist of one house only (legislative council).

- Act separated for the first time the provincial and central budgets, with provincial legislatures being authorized to make their budgets.

- A High Commissioner for India was appointed, who was to hold his office in London for six years and whose duty was to look after Indian trade in Europe.

- Secretary of State for India who used to get his pay from the Indian revenue was now to be paid by the British Exchequer, thus undoing an injustice in the Charter Act of 1793.

- Though Indian leaders for the first time got some administrative experience in a constitutional set-up under this Act.

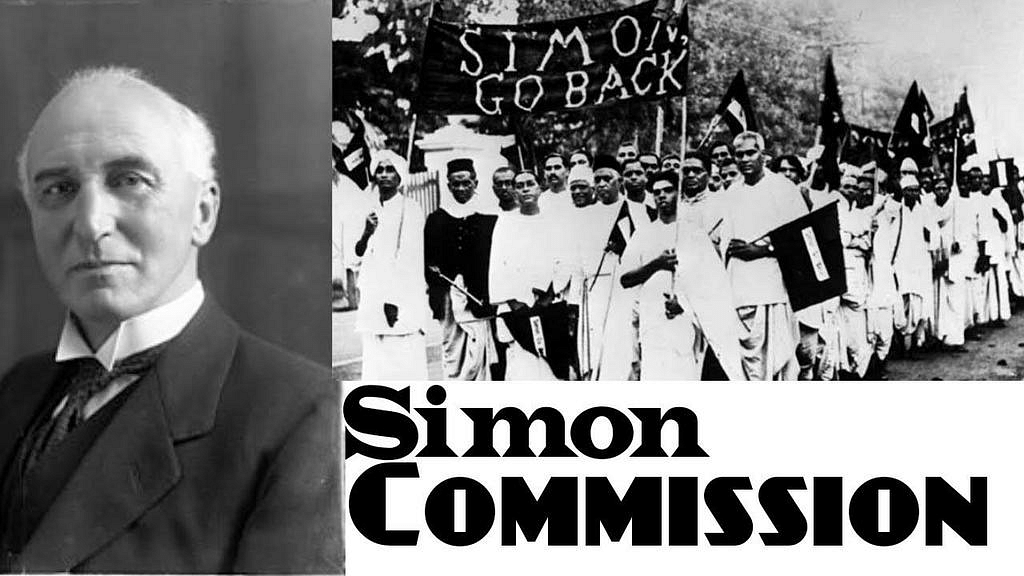

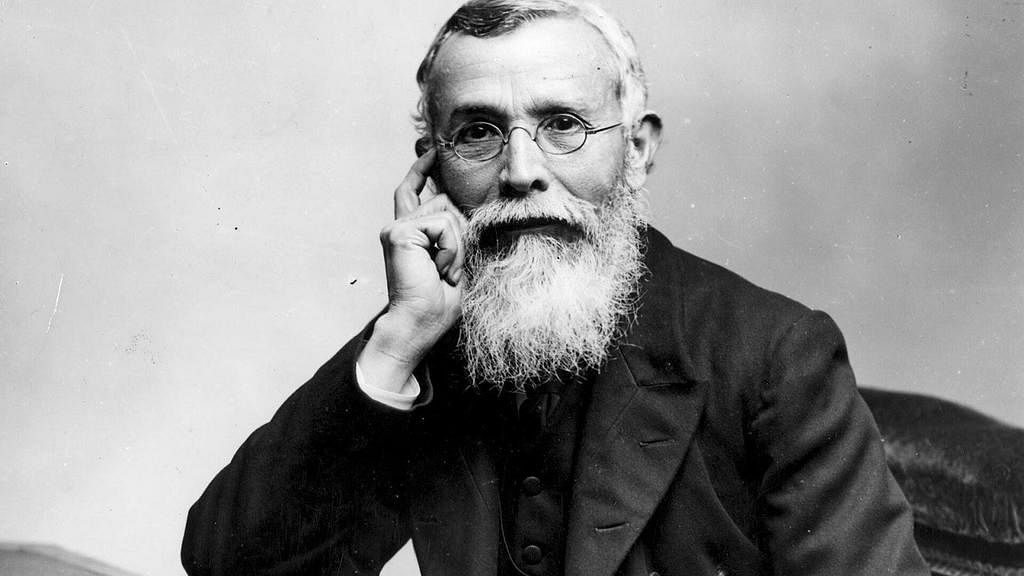

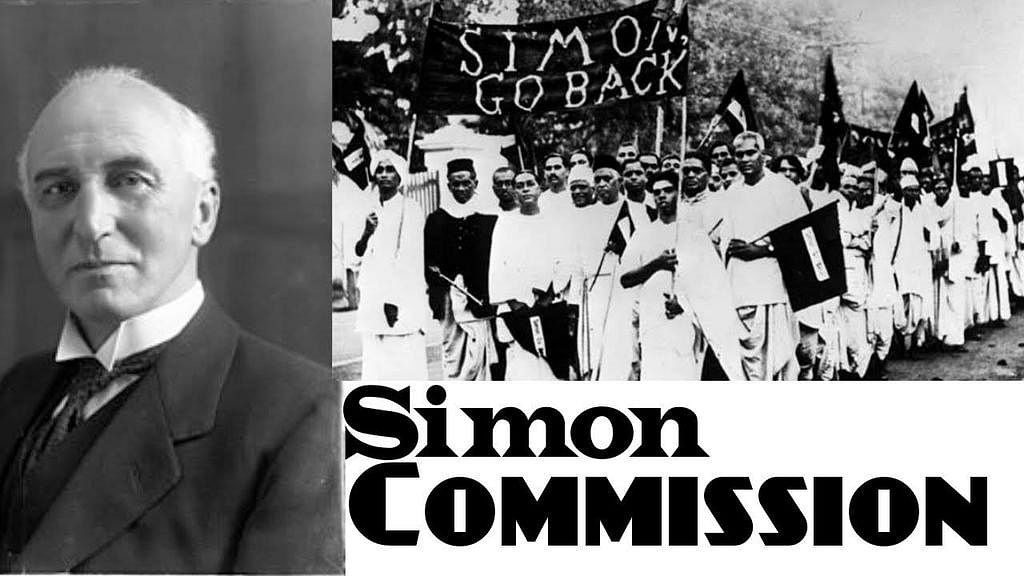

The Indian Statutory Commission also known as Simon Commison’, was a group of seven Members of Parliament under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon (later, 1st Viscount Simon).

- The commission arrived in British India in 1928 to study constitutional reform in Britain’s largest and most important possession.

- 1919 Act had provided that a Royal Commission would be appointed ten years after the Act to report on its working. Three Round Table Conferences were called by the British government to consider the proposals.

- Subsequently, a White Paper on Constitutional Reforms was published by the British government in March 1933

The Government of India Act was passed by the British Parliament in August 1935. It was the longest act enacted by the British Parliament at that time. So, it was divided into two separate acts namely, the Government of India Act 1935 and the Government of Burma Act 1935.

- Act, with 451 clauses and 15 schedules, contemplated the establishment of an All- India Federation in which Governors’ Provinces and the Chief Commissioners’ Provinces and those Indian states which might accede to be united were to be included.

- Dyarchy, rejected by the Simon Commission, was provided for in the Federal Executive.

- Federal Legislature was to have two chambers (bicameral)—the Council of States and the Federal Legislative Assembly. The Council of States (the Upper House) was to be a permanent body.

- There was a provision for joint sitting in cases of deadlock between the houses. There were to be three subject lists— the Federal Legislative List, the Provincial Legislative List and the Concurrent Legislative List. Residuary, legislative powers were subject to the discretion of the governor-general.

- Dyarchy in the provinces was abolished and provinces were given autonomy

- Provincial legislatures were further expanded. Bicameral legislatures were provided in the six provinces of Madras, Bombay, Bengal, United Provinces, Bihar and Assam, with other five provinces retaining unicameral legislatures.

- Principles of'communal electorates’ and 'weightage' were further extended to depressed classes, women and labour.

- Franchise was extended, with about 10 per cent of the total population getting the right to vote.

- Act also provided for a Federal Court (which was established in 1937), with original and appellate powers, to interpret the 1935 Act and settle inter-state disputes, but the Privy Council in London was to dominate this court. India Council of the Secretary of State was abolished.

- All-India Federation as visualised in the Act never came into being because of the opposition from different parties of India. The British government decided to introduce the provincial autonomy on April 1,1937, but the Central government continued to be governed in accordance with the 1919 Act, with minor amendments. The operative part of the Act of 1935 remained in force till August 15, 1947.

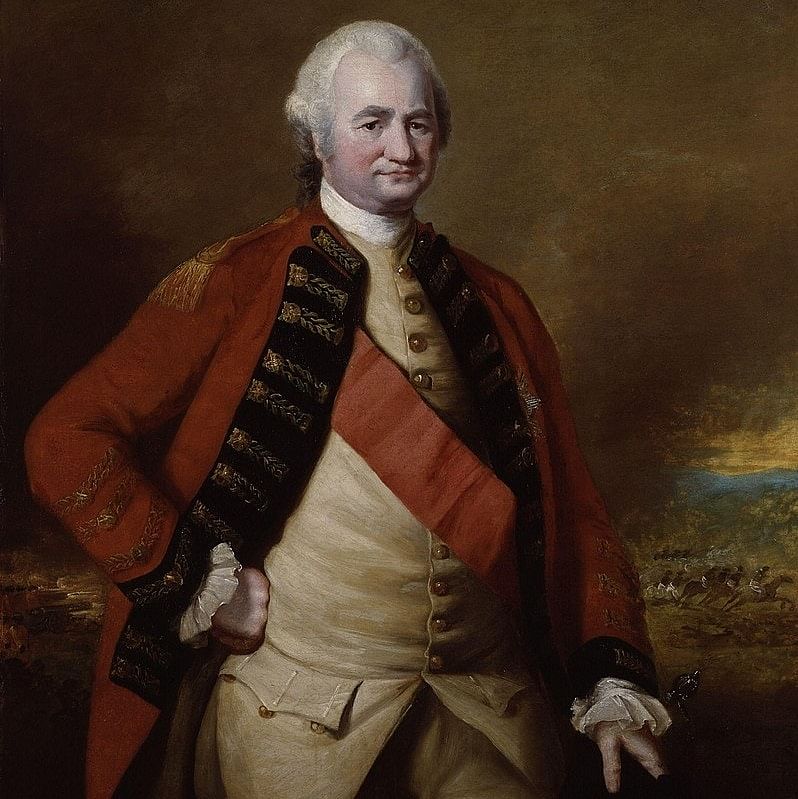

Lord Cornwallis in India

Lord Cornwallis in India

- Cornwallis (governor-general, 1786-93) was the first to bring into existence and organize civil services. He tried to check corruption through

- Raising the civil servants’ salary,

- Strict enforcement of rules against private trade,

- Debarring civil servants from taking presents, bribes, etc.,

- Enforcing promotions through seniority.

Lord Wellesley

Lord Wellesley

- Wellesley (governor-general, 1798-1805) set up Fort William College for the training of new recruits. In 1806 Wellesley’s college was disapproved by the Court of Directors and instead the East India College was set up at Haileybury in England to impart two years’ training to the recruits.

- The reasons for the exclusion of Indians were

(i) Belief that only the English could establish administrative services serving British interests;

(ii) Belief that the Indians were incapable, untrustworthy, and insensitive to the British interests;

(iii) Fact there was high competition among the Europeans themselves for lucrative posts, so why offer them to the Indians.

- The maximum permissible age was gradually reduced from 23 (in 1859) to 22 (in 1860) to 21 (in 1866) and to 19 (1878).

- In 1863, Satyendra Nath Tagore became the first Indian to qualify for the Indian Civil Service.

- In 1878-79, Lytton introduced the Statutory Civil Service consisting of one-sixth of covenanted posts to be filled by Indians

- The Indian National Congress raised the demand, after it was set up in 1885, for

(i) lowering of age limit for recruitment, and

(ii) Holding the examination simultaneously in India and Britain. - The Aitchison Committee on Public Services (1886), set up by Dufferin. recommended—

(i) The dropping of the terms covenanted’ and "uncovenanted’;

(ii) Classification of the civil service into Imperial Indian Civil Service (examination in England), Provincial Civil Service (examination in India), and Subordinate Civil Service (examination in India); and, raising the age limit to 23.

(iii) In 1893, the House of Commons in England passed a resolution supporting the holding of simultaneous examination in India and England; but the resolution was never implemented.

- The Montford reforms— i. Stated a realistic policy recommended holding of simultaneous examination in India and England. ii. recommended that one-third of recruitments be made in India itself—to be raised annually by 1.5 percent.

- The Lee Commission recommended that

(i) secretary of state should continue to recruit the ICS, the Irrigation branch of the Service of Engineers, the Indian Forest Service, etc.;

(ii) recruitments for the transferred fields like education and civil medical service be made by provincial governments;

(iii) direct recruitment to ICS on basis of 50:50 parity between the Europeans and the Indians be reached in 15 years;

(iv) a Public Service Commission be immediately established

- 1935 Act recommended the establishment of a Federal Public Service Commission and Provincial Public Service Commission under their spheres.

- This was done in mainly two ways. Firstly the maximum age for appearing at the examination was reduced from twenty-three in 1859 to nineteen in 1878 under Lytton. Secondly, all key positions of power and authority and those which were well-paid were occupied by the Europeans.

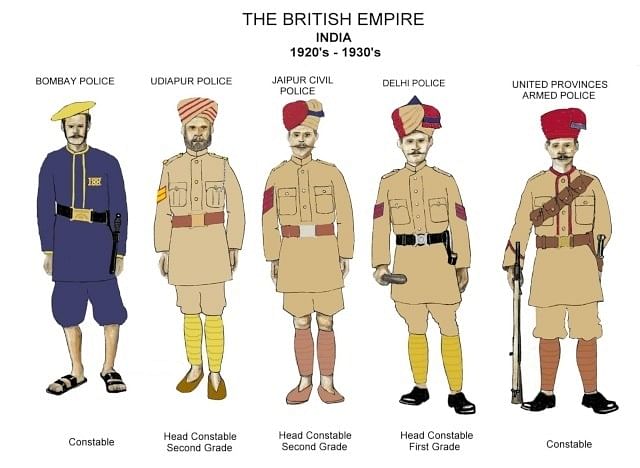

- Watch guards since time immemorial protecting villages at night. Under the Mughal rule, there were the faujdars and mails. The kotwal was responsible for the maintenance of law and order in the cities. In Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa between 1765 and 1772 the zamindars were expected to maintain the staff including thanedars In 1775, faujdar thanas were established

- 1791 Cornwallis organized a regular police force to maintain law and order by going back to and modernizing the old Indian system of thanas (circles) in a district under a daroga (an Indian) and a superintendent of police (SP).1808 Mayo appointed an SP for each division helped by a number of spies (goyendas)

- Recommendations of the Police Commission (1860) led to the Indian Police (i) Act, 1861. The commission recommended—

A system of civil constabulary—maintaining the village set-up in the present form (a village watchman maintained by the village) but the indirect relationship with the rest of the constabulary.

(ii) Inspector-general as the head in a province, deputy inspector-general as the head in a range, and SP as the head in a district. - 1902 The Police Commission recommended the establishment of CID

- Prior to the revolt of 1857, there were two separate sets of military forces under British control, which operated in India. The first set o: I units, known as the Queen's army, were the serving troops on duty in India. The other was the Company's troops—a mixture of European regiments of Britons and Native regiments recruited locally from India but with British officers. The Queen’s army was part of the Crown's military force.

- On the whole, the British Indian Army remained a costly military machine.

- The beginning of a common-law system, based on recorded judicial precedents, can be traced to the establishment of 'Mayor s Courts' in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta in 1726 by the East India Company.

- Reforms under Warren Hastings (1772-1785)-

(i) District Diwani Adalats were established in districts to try civil disputes. These adults were placed under the collector and had Hindu law applicable for Hindus and the Muslim law for Muslims. The appeal from District Diwani Adalats lay to the Sadar Diwani Adalat which functioned under a president and two members of the Supreme Council.

(ii) District Fauzdari Adalats were set up to try criminal disputes and were placed under an Indian officer assisted by qazis and muftis. These adults also were under the general supervision of the collector. Muslim law was administered in Fauzdari Adalats.

(iii) Under the Regulating Act of 1773, a Supreme Court was established at Calcutta which was competent to try all British subjects within Calcutta and the subordinate factories, including Indians and Europeans. It had original and appellate jurisdictions. Often, the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court clashed with that of other courts.

- Circuit courts were established at Calcutta, Dacca, Murshidabad, and Patna. These circuit courts had European judges and were to act as courts of appeal for both civil and criminal cases.

- Sadar Nizamat Adalat was shifted to Calcutta and was put under the governor-general and members of the Supreme Council assisted by the chief qazi and the chief mufti. The District Diwani Adalat was now designated as the District, City, or the Zila Court and placed under a district judge. The collector was now responsible only for the revenue administration with no magisterial functions.

- A gradation of civil courts was established (for both Hindu and Muslim laws)

(i) Munsiff s Court under Indian officers,

(ii) Registrar’s Court under a European judge,

(iii) District Court under the district judge,

(iv) Four Circuit Courts as provincial courts of appeal,

(v) Sadar Diwani Adalat at Calcutta, and

(vi) King-in-Council for appeals of 5000 pounds and above. - The Cornwallis Code was laid out

(i) There was a separation of revenue and justice administration.

(ii) European subjects were also brought under jurisdiction.

(iii) Government officials were answerable to the civil courts for actions done in their official capacity.

(iv) Principle of the sovereignty of law was established.

- Four Circuit Courts were abolished and their functions transferred to collectors under the supervision of the commissioner of revenue and circuit.

- Sadar Diwani Adalat and Sadar Nizamat Adalat were set up at Allahabad for the convenience of the people of Upper Provinces.

- Till now, Persian was the official language in courts. Now, the suitor had the option to use Persian or a vernacular language, while in the Supreme Court, the English language replaced Persian.

- 1833: A Law Commission was set up under Macaulay for the codification of Indian laws. As a result, a Civil Procedure Code (1859), an Indian Penal Code (1860), and a Criminal Procedure Code (1861) were prepared.

- 1860: It was provided that the Europeans can claim no special privileges except in criminal cases, and no judge of an Indian origin could try them.

- 1865: Supreme Court and the Sadar Adalats were merged into three High Courts at Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras.

- 1935: The government of India Act provided for a Federal Court (set up in 1937) which could settle disputes between governments and could hear limited appeals from the High Courts.

- Rule of law was established.

- Codified laws replaced the religious and personal laws of the rulers.

- Even European subjects were brought under the jurisdiction, although in criminal cases, they could be tried by European judges only.

- Government servants were made answerable to the civil courts.

- The judicial system became more and more complicated and expensive. The rich could manipulate the system.

- There was ample scope for false evidence, deceit, and chicanery.

- Dragged out litigation meant delayed justice.

- Courts became overburdened as litigation increased

- Often, the European judges were not familiar with the Indian usage and traditions.

- The genesis of Administrative Changes: New Stage of Colonialism-There was a renewed upsurge of imperial control and imperialist ideology which was reflected in the reactionary policies during the vice-royalties of Lytton, Dufferin, Lansdowne, Elgin, and, above all, Curzon. The changes in the governmental structure and policies in India were to shape the destiny of modern India in many ways.

- Act for Better Government of India, 1858 transferred the power to govern from the East India Company to the British Crown.

- (ii) By the Indian Councils Act, 1861, a fifth member, who was to be a jurist, was added to the viceroy’s executive council. The legislative council so constituted possessed no real powers and was merely advisory in nature. Its weaknesses were as follows:

- It could not discuss important matters and no financial matters at all without the previous approval of the Government.

- It had no control over the budget.

- It could not discuss executive action.

- The final passing of the bill needed the viceroy’s approval.

- Even if approved by the viceroy, the secretary of state could disallow legislation.

- Indians associated as non-officials were members of elite sections only— princes, landlords, diwans, etc.—and were not representative of the Indian opinion.

- Viceroy could issue ordinances (of 6 months validity) in case of emergency.

- The Indian Councils Act, 1861 returned the legislative powers to the provinces of Madras and Bombay which had been taken away in 1833.

- There were many factors that made it necessary for the British government in India to work towards establishing local bodies.

- Financial difficulties faced by the Government, due to over-centralization, made decentralization imperative.

- It became necessary that modern advances in civic amenities in Europe be transplanted in India considering India’s increasing economic contacts with Europe.

- The rising tide of nationalism had improvement in basic facilities as a point on its agenda.

- A section of British policy-makers saw the association of Indians with the administration in some form or the other, without undermining the British supremacy in India, as an instrument to check the increasing politicization of Indians.

- The utilization of local taxes for local welfare could be used to counter any public criticism of British reluctance to draw upon an already overburdened treasury or to tax the rich upper classes.

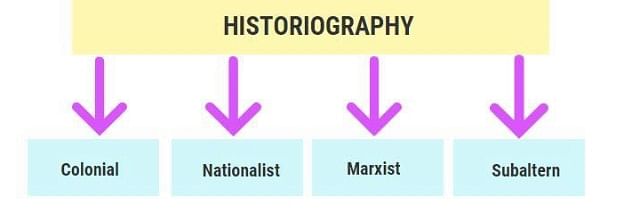

The modern history of India, for the convenience of understanding, can be broadly read under four approaches—the Colonial (or the Imperialist), Nationalist, Marxist, and Subaltern—each with its own distinct characteristics and modes of interpretation.

Classification of Modern History

Classification of Modern History

However, there are other approaches — Communalist, Cambridge, Liberal and Neo-liberal, and Feminist interpretations — which have also influenced historical writing on modern India.

The production of histories of India has become very frequent in recent years and may well call for some explanations. The reason is a two-fold one: changes in the Indian scene requiring a reinterpretation of the facts and changes in the attitudes of historians orb essential elements of Indian history. - Percival Spear

For the major part of the 19th century, the Colonial School occupied a high position in India. The term "colonial approach" has been used in two senses. One relates to the history of the colonial countries, while the other refers to the works which were influenced by the colonial ideology of domination. It is in the second sense that most historians today write about colonial historiography.

Colonial Historiography

Colonial Historiography Certain characteristics common to most of the works of these historians are the following:

(i) 'Orientalist' representation of India.

(ii) The opinion that the British brought unity to India.

(iii) The notions of Social Darwinism—the English considered themselves superior to the "natives" and the fittest to rule.

(iv) India viewed as a stagnant society which required guidance from the British (White Man's burden).

(v) Establishing Pax Britannica to bring law and order and peace to a bickering society.

- The nationalist approach to Indian history can be described as one which tended to contribute to the growth of nationalist feelings and to unify people in the face of religious, caste, or linguistic differences or class differentiation. This approach looks at the national movement as a movement of the Indian people, which grew out of the growing awareness among all people of the exploitative nature of the colonial rule.

- This approach developed as a response to and in confrontation with the colonial approach. It should be noted that the nationalist historians of modern India didn’t exist before 1947. Before 1947, nationalist historiography mainly dealt with the ancient and medieval periods of Indian history.

- The only accounts of the national movement were by nationalist leaders (not historians) such as R.G. Pradhan, A.C. Mazumdar, J.L. Nehru, and Pattabhi Sitaramayya. R.C. Majumdar and Tara Chand are noted nationalist historians of modern India.

- The beginning of the Marxist approach in India was heralded by two classic books—Rajni Palme Dutt’s India Today and A.R. Desai’s Social Background of Indian Nationalism. Originally written for the famous Left Book Club in England, India Today, first published in 1940 in England, was later published in India in 1947. A.R. Desai's Social Background of Indian Nationalism was first published in 1948.

- Unlike the imperialist/colonial approach, the Marxist historians clearly see the primary contradiction between the interests of the colonial masters and the subject people, as well as the process of the nation-in-the-making. Unlike the nationalists, they also take full note of the inner contradictions between the different sections of the people of the Indian society.

- This school of thought began in the early 1980s under the editorship of Ranajit Guha, as a critique of the existing historiography, which was faulted for ignoring the voice of the people.

- Right from the beginning, subaltern historiography took the position that the entire tradition of Indian historiography had had an elitist bias.

- For the subaltern historians, the basic contradiction in Indian society in the colonial epoch was between the elite, both Indian and foreign, on the one hand, and the subaltern groups, on the other, and not between colonialism and the Indian people.

Subaltern historiography, the working class and social theory for the global south

Subaltern historiography, the working class and social theory for the global south- A few historians have of late initiated a new trend, described by its proponents as subaltern, which dismisses all previous historical writing, including that based on a Marxist perspective, as elite historiography, and claims to replace this old, 'blinkered' historiography with what it claims is a new people's or subaltern approach — Bipan Chandra.

- Nationalism, say the subalterns, ignored the internal contradictions within the society as well as what the marginalised represented or had to say. They believe that the Indian people were never united in a common anti-imperialist struggle, that there was no such entity as the Indian national movement.

- The historians of this school, relying completely on the colonial historiography of medieval India and colonial-era textbooks, viewed Hindus and Muslims as permanent hostile groups whose interests were mutually different and antagonistic to each other.

Communalism

Communalism - This view was not only reflected in the writings of the historians but it also found a more virulent form in the hands of the communal political leaders.

- Fundamental contradiction under colonial rule was among the Indians themselves.

- It takes the mind or ideals out of human behaviour and reduces nationalism to 'animal politics'.

- According to this interpretation, the economic exploitation of the colonies was not beneficial to the British people as a whole.

- The availability of markets for British industrial goods in the colonial world and capital investment in overseas markets (like laying of railways in India) might have actually discouraged domestic investment and delayed the development of the 'new' industries in Britain.

The shift in terms of the writing of women’s history began with the women’s movement of the 1970s which provided the context and impetus for the emergence of women’s studies in India. Very soon, women's history broadened and assumed the more complex shape of gender history. Feminist Historiography

Feminist Historiography

In the colonial period, two works based upon the women’s question in India—The High Caste Hindu Woman (1887) by Pandita Ramabai, and Mother India (1927) by Katherine Mayo—attracted international attention.

Educational Policies and Growth of Modern Education:

The British East India Company showed very little interest in the education of its subjects during this period, the only two minor exceptions being:

- The Calcutta Madrasah set up by Warren Hastings in 1781 for the study and teaching of Muslim law and related subjects, and

- The Sanskrit College at Varanasi by Jonathan Duncan in 1792 for the study of Hindu law and philosophy.

Sanskrit College Varanasi

Sanskrit College Varanasi

Both were designed to provide a regular supply of qualified Indians to help the administration of law in the Courts of the Company.

- Due to the strong pressure exerted on the Company by the Christian missionaries and many humanitarians, including some Indians, to encourage and promote modern education in India, the Charter Act of 1813 required the Company to spend rupees one lakh annually for encouraging learned Indians and promoting the knowledge of modern sciences in India.

- Two controversies about the nature of education arose during the first part of this phase. They were:

- Whether to lay emphasis on the promotion of modern western studies or on the expansion of traditional Indian learning?

- Whether to adopt Indian languages or English as the medium of instruction in modern schools and colleges to spread western learning?

- These two controversies were settled in 1835 when Lord William Bentinck with the support of Rammohan Roy and other reformers, decided to devote the limited resources to the teaching of Western sciences and literature through the medium of English alone.

- In 1844 Lord Hardinge decided to give government employment to Indians educated in English schools. The success of English education was thus assured and it made good progress in the three presidencies of Bengal, Bombay and Madras where a number of schools and colleges were opened between 1813 and 1853.

- Three other developments also took place during this phase. They are:

- A great upsurge in the activities of the missionaries who did pioneer work in almost every field of modern education;

- Establishment of medical, engineering, and law colleges, which marked a beginning in professional education; and

- Official sanction accorded to the education of girls (Lord Dalhousie, in fact, offered the open support of government).

- The Government policy of opening a few English schools and colleges instead of a large number of elementary schools led to the neglect of the education of the masses. This was so because the government was not willing to spend more than an insignificant sum on education.

- To cover up this defect in their policy, the British took recourse to the so-called “Downward Filtration Theory” which meant that education and modern ideas were supposed to filter or radiate downwards from the upper classes.

- In other words, the few educated persons from the upper and middle classes were expected to assume the task of educating the masses and spreading modern ideas.

- This policy continued until the very end of the British rule in practical terms, though it was officially (in theory only) abandoned in 1854.

- The Educational Despatch of 1854, also known as Wood’s Despatch (because it was drafted by Sir Charles Wood, the then President of the Board of Control, who later became the first Secretary of State for India) and generally considered as the “Magna Carta of English Education in India”, formed a landmark in the history of modern education in India.

- For it outlined a comprehensive plan which supplied the basis for the subsequent development of the education system in India.

- This despatch rejected the “filtration theory” and laid stress on mass education, female education and improvement of vernaculars, and favoured secularisation of education and a coordinated system of education from the lowest level (primary school) to the highest stage (university).

- The second half of the 19th century witnessed the gradual implementation of the policies laid down by the Despatch of 1854.

- Creation of Education Departments in the provinces of Bombay, Madras, Bengal, North-Western Provinces and Punjab in 1855 and later in the new provinces which were formed at a later date; organization of the Indian Education Service in 1897 to cover the senior-most posts.

- Establishment of the Universities of Calcutta (January 1857), Bombay (July 1857), Madras (September 1857), Punjab (1882), and Allahabad (1887).

- The Indian Education Commission of 1882, generally known as a Hunter Commission (Sir W.W. Hunter was its president) was appointed by Lord Ripon to enquire into the manner in which effect had been given to the principles of the Despatch of 1854 and to make the necessary recommendations with regard to the primary education (which was the chief object of its inquiry), the Commission recommended that the newly founded local bodies (district boards and municipalities) should be entrusted with the management of primary schools.

- And with regard to the private enterprise, it recommended that the Government should maintain only a few colleges, secondary schools and other essential institutions, and the rest of the field should be left to private enterprise.

- These recommendations, along with others, of the Commission, were accepted by the government and implemented.

- Lord Curzon convened the first conference of Directors of Public Institution in 1901 and initiated an era of educational reform based on its decisions.

- He appointed a Universities Commission under Thomas Raleigh (Law Member of the Viceroy's Executive Council) in 1902, and based on its recommendations Indian Universities Act of 1904 was passed.

- The Act enabled the universities to assume teaching functions (hitherto they were mainly examining bodies), constituted syndicates for the speedier transaction of business, provided for strict conditions of affiliation and periodic inspection of the different institutions.

- All these provisions led to a substantial measure of qualitative improvement in higher education, though the Act was severely criticized by the nationalist Indians for its tightening governmental control over universities.

- In 1910 a separate Department of Education was established at the Centre, and in 1913 the Government of India Resolution on Education Policy called for the opening of residential universities and wanted to improve the training of teachers for primary and secondary schools.

- The Sadler Commission was appointed by Lord Chelmsford to review the work of Calcutta University. Its main recommendations were:

- Secondary education should be left to the control of a Board of Secondary Education and the duration of the degree course should be 3 years, etc.

- By 1921 the number of Universities in India increased to 12, the seven new ones being Banaras, Mysore Patna, Aligarh, Dacca, Lucknow, and Osmania.

- Similar growth could be seen at the secondary and primary levels of education, though this growth rate was hardly sufficient for the purpose of mass education.

- It was also during this phase that the concept of national education was coined for the first time by leaders like Gandhi, Lala Lajpat Rai, Annie Besant, etc. According to them, the existing system of education was unhelpful and even antagonistic to national development, and hence a new system capable of fostering love of the motherland should be evolved.

- Accordingly, a number of national institutions, such as Kasi Vidyapith and Jamia Millia Islamia, were established, and they worked independently of the official system.

- During this phase, education for the first time officially came under Indian control in the sense that it became, under the provisions of the Montford Act of 1919 (and the resultant Diarchical provincial governments), a provincial transferred subject administered by a minister responsible to the provincial legislature. As a result, there was unprecedented expansion at all levels of education.

- Increase in the number of Universities (20 in 1947); improvement in the quality of higher-level education due to the introduction of reforms based largely on the recommendations of the Sadler Commission; establishment of an Inter-University Board (1924) and beginning of inter-collegiate and inter-university activities.

- Significant achievements in the field of women’s education and the education of the backward classes due to the liberal concessions given to them by the popular ministries.

Coastal Kingdoms and Silk Route:

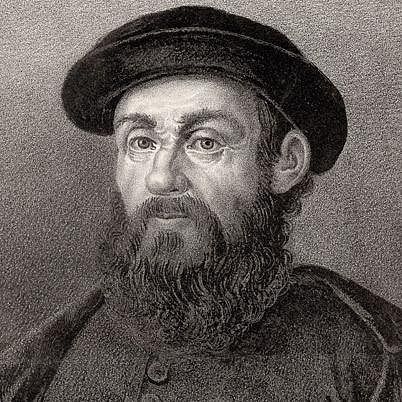

The Silk Road was a network of historic trade routes that connected the ancient globe through trade between 130 BCE and 1453 CE. It was originally created under the Han Dynasty of China. Although the term “Silk Road” is frequently used, historians prefer the term “Silk Routes” because the Silk Road was not a single route that connected the east and the west. These routes were traveled by the European adventurer Marco Polo (1254–1324 CE), who wrote a comprehensive account of them in his well-known work.

The Silk Road, also known as the Silk Route, was a network of ancient commercial routes that connected East and West from China to the Mediterranean Sea and served as a major conduit for cultural exchange.

- The flourishing traffic in Chinese silk that took place across its length beginning in the Han era (207 BCE – 220 CE) gave rise to the term “Silk Road”. Around 114 BCE, the Han dynasty extended the trade routes through Central Asia, primarily as a result of the travels and missions of Zhang Qian, a Chinese imperial envoy.

- As a result of trade along the Silk Road, long-distance political and economic ties between the civilizations of China, the Indian subcontinent, Persia, Europe, the Horn of Africa, and Arabia were established.

- Although silk was undoubtedly the main export from China, the Silk Routes also saw the exchange of several other items, as well as syncretic ideas, numerous technology, religions, and diseases. The Silk Road was used by the civilizations along its network to conduct cultural exchange alongside commercial trade.

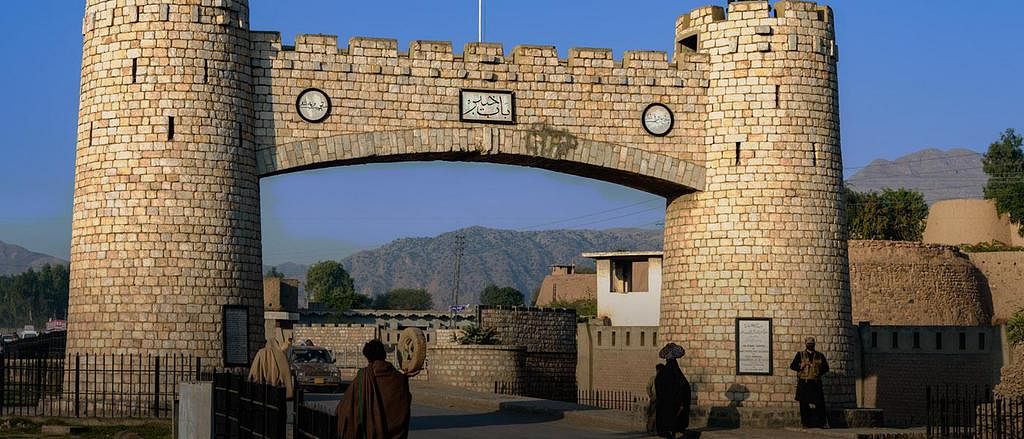

Several routes made up the Silk Road. The Northern route, the Southern route, and the Southwestern route were the most popular overland routes.

Northern route

The Chinese Emperor Wu of Han, who ruled from 141 to 87 BC, employed his army to prevent nomadic tribes from harming travelers inside his zone of influence, which led to the northern route becoming more and more popular during the first century BC.

Southern route

The southern route from China passed through the Karakoram mountains. As a result, it was sometimes referred to as the Karakoram route. The Karakoram mountain range stretches into Afghanistan and Tajikistan in the northwest and crosses the frontiers of Pakistan, India, and China.

Since many travelers preferred to continue by ship rather than traveling overland, the southern route had numerous spurs reaching south to the sea, west of the Karakoram mountains.

Southwestern route

The Ganges Delta was traversed on the southwesterly route between China and India. Archaeological digs in this delta region, which served as a significant commerce hub, uncovered a staggering variety of items from all over the world, including antique Roman beads and gemstones from Thailand and Java.

The Silk Road emerged as the most significant access route in the globalization of the ancient world.

- From 600 to 1200 AD, the Silk Road served as the main route for trade and the connection between Eastern and Western cultures.

- The roadway provided once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for traders, pilgrims, soldiers, explorers, and adventure seekers.

- With departure points in Asia, India, and gradually connecting sea channels all over the region, the ancient Silk Road, a network of commerce routes that spanned more than 4,600 miles, served as a conduit for trade.

- The Silk Road was the most significant and extensive land trade route in human history that connected the most developed and mighty civilizations of the world, the majority of which were concentrated on the Mediterranean and the Yellow and Yangtze River basins.

- Over the course of the centuries-long Silk Road trade, silk and porcelain that belonged to China were the two most popular goods. Given its lightweight, ease of transportation, and reputation of being worth its weight in gold during the Roman era, silk became the most valuable export along the Silk Road. The road, thus aided China’s economic growth and wealth creation.

- Technologies that changed the world spread westward along the Silk Road from the Han era, around 139 BC till the end of the Yuan Empire, in 1368.

- Religions traveled along the Silk Road routes in an eastward direction despite the general westward movement of technology. From the Han era onward, Buddhism had a significant impact on China owing to the introduction of Central Asian-style Buddhism. The advent of Western religions altered civilization as a result.

- While major crops and domesticated animals moved mostly eastward, technology spread primarily westward. To acquire the larger horse breeds, the Han Emperor launched trade along the Silk Road in the year 139 BC. Population increase was largely driven by the eastward spread of crops and animals.

- During the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912), ships moved goods much more efficiently and quickly, rendering the Silk Road land routes obsolete. The Silk Road was then forcibly reopened during the Japanese conquest of China in the 1930s since the Japanese controlled the sea lanes and ports. The Soviet Union provided the Chinese troops with weapons from 1937 to 1941. China was therefore saved which could directly be attributed to the Silk Road.

Silk was transported by traders from China to Europe, where it was worn by aristocrats and wealthy clients. The Silk Road network was crucial for the migration of people, the transmission of philosophy, science, technology, and creative ideas, in addition to the trading of a broad variety of items other than just silk.

Other items that were exchanged over the Silk Road include:

- Ginger, lacquerware, porcelain, and silk fabrics from China

- Sandalwood from India

- Persian dates, pistachios, and saffron from Persia

- frankincense and myrrh from Somalia

- Glass bottles from Egypt

- Fur from Caucasian steppe’s animals

- Spices from the East Indies

- Rome-made glass beads

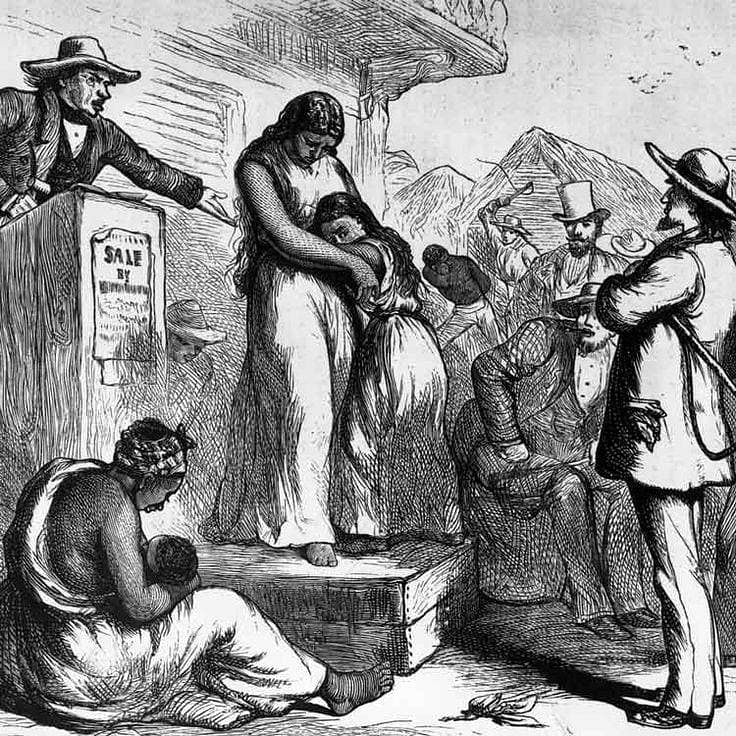

- A terrible slave trade also took place along the magnificent Silk Road.

- Along the Silk Road, in addition to tangible goods, religion and technology were also “traded.”

- The Silk Road was most valuable for its cultural exchange.

- Each and every aspect of civilization including art, religion, philosophy, technology, language, science, and architecture was shared along these trade routes together with the goods that merchants transported from one nation to another.

- The outbreak of the bubonic plague, which is assumed to have reached Constantinople via the Silk Road and devastated the Byzantine Empire in 542 CE, is proof that diseases also traveled along this route.

- Due to the closure of the Silk Road, traders were compelled to conduct their business through the sea, which ushered in the Age of Discovery and the emergence of a global community.

- The shutdown of the Silk Road prompted Europeans to discover and ultimately conquer the so-called New World of the Americas, thereby establishing the so-called Columbian Exchange, through which commodities and values were carried from those in the Old World to those in the New World, always to the detriment of the native people of the New World.

- The Silk Road served to widen people’s perception of the world they lived in.

Through the first millennium B.C., the Silk road served as a significant trade route.

- It linked the Kamboja kingdom, which encompasses modern-day Afghanistan and Tajikistan, to ancient Pratishthana, which included Paithan on the Godavari in the south, towns and cultural hubs in northern India, and Tamralipti or Tamluk on the eastern coastline.

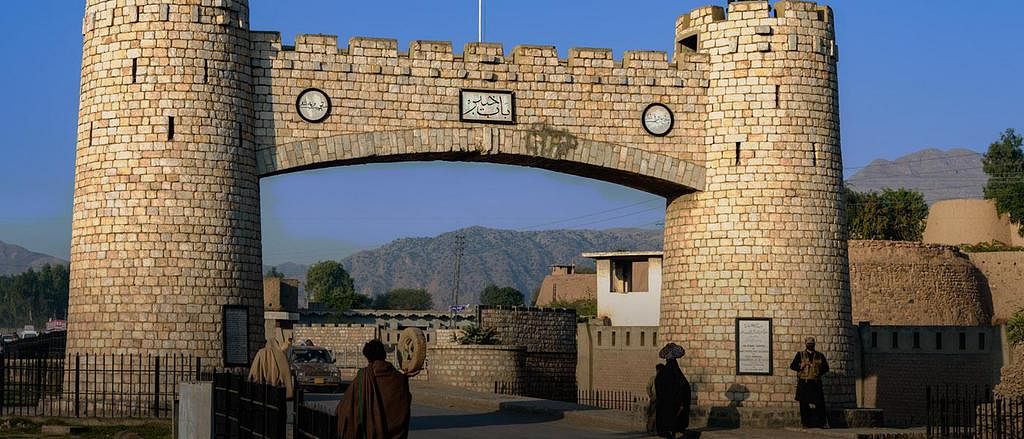

- India had three potential pathways that linked to the Silk Road. The Silk Road was eventually joined by three routes, first which went through Hadda, Kapisa, and Bamiyan, the second passed through Srinagar, Gilgit, and the Karakoram Range and the last route passed through Purushapura. The aforementioned routes were used for trade and pilgrimage by both foreigners and Indians.

- From Uttarapatha, a significant route connected the Silk Road via Yunnan and Burma. The trade with south-western China was conducted over this route. This is demonstrated by the story of King Chiang Kein (c. 127 BC), who discovered textiles and bamboo from southwest China being sold in the Gandhara market. He discovered via personal research that these products were transported from Yunnan, Burma, to Bengal in eastern India, where they were subsequently transported through the Uttarapatha via Afghanistan and India to Bactria.

- It was not silk that was the most important item transported along this route, but rather, religion. Along the northern branch of the road, Buddhism migrated from India to China and central Asian nations. The first influences appeared during the initial exploration of the passes across the Karakoram.

- Over the course of around 1,500 years, trade along the Silk Road persisted. When the Mongols ruled throughout Eurasia from the Chinese Yuan Empire (1279–1368) to Eastern Europe, trade increased and reached a peak.

- The Silk Road trade in the 1400s was effectively put to an end by the fall of the Yuan Empire, growing isolationism during the reign of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), growth of silk manufacturing in Europe and other regions, and expansion of marine trade.

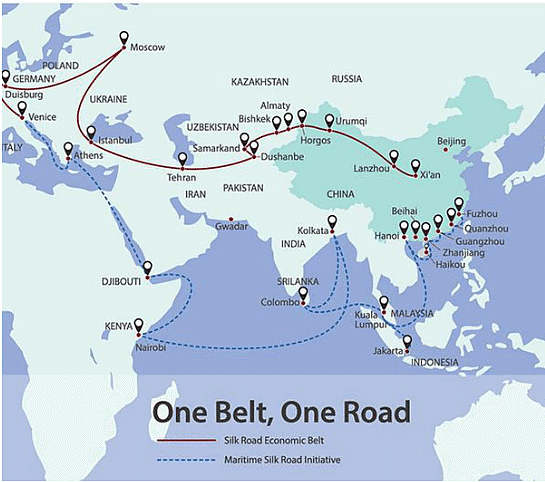

- A new Silk Road is emerging within the Silk Road’s historical background. The Belt and Road Initiative, also known as the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, was introduced by China in 2013. It focuses on encouraging shared wealth and progress.

- Infrastructure for new trans-Asian transportation: The first freight trains from Europe to China started operating in 2011, reducing the 50-day maritime transit time from Germany to China to just 18 days.

- A significant 5,400-kilometer motorway from St. Petersburg to the Yellow Sea was constructed in 2018, enabling travel across the route to take just ten days. This is a new means of transportation for sightseeing and affordable tourism across Silk Road locations.

- The Silk Road is now a well-liked travel route. Silk Road tourism is expanding in Xinjiang as well as all along the route from Xi’an to Kashgar and Altay in Xinjiang to Greece and Albania.

In this EduRev document, you will read about the advent of other European powers and how the British overpowered them and became a dominant power in India.

- After the decline of the Roman Empire in the seventh century, the Arabs established dominance in Egypt and Persia, leading to a decline in direct contact between Europe and India.

- Easy accessibility to Indian commodities like spices, calicoes, silk, and precious stones was greatly affected.

- In 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks, making the Red Sea trade route a lucrative state monopoly for Islamic rulers.

- Arabs also controlled the land routes to India.

- The fifteenth-century spirit of the Renaissance in Europe led to increased prosperity and demand for oriental luxury goods.

- Prince Henry of Portugal, nicknamed the 'Navigator,' significantly promoted exploration.

- The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 divided the non-Christian world between Portugal and Spain along an imaginary line in the Atlantic.

- Portugal could claim and occupy everything east of the line, while Spain could claim everything west of it.

- The Viceroy of Portuguese possessions in India, Francisco de Almeida, opposed establishing a territorial empire in India, preferring that the Portuguese maintain supremacy at sea and limit their activities to purely commercial transactions. This is known as the Blue Water Policy.

- In order to protect Portuguese interests, King Ferdinand I of Portugal appointed a three-year governor in India and provided him with sufficient troops in 1505.

- By conquering Aden, Ormuz, and Malacca, the newly appointed governor, Francisco De Almeida, was tasked with strengthening the Portuguese position in India and obliterating the Muslim trade.

- Only 8 ships left when Francisco de Almeida arrived at Cochin on October 31, 1505.

- While he was there, he discovered that the Portuguese traders at Quilon had been massacred. He sent his son Lourenço with six ships to attack Quilon’s harbor, where they indiscriminately sank Calicut boats.

- Francisco De Almeida wanted to create Portugal as a powerful nation in the maritime region under this strategy.

- He took control of Goa from the Sultan of Bijapur.

- In 1510 AD, Albuquerque was succeeded by Francisco De Almeida.

- Later, Goa became the headquarters of Portuguese settlements in India.

- The Navy’s dominance and control over the coastal regions helped to build the Portuguese in India.

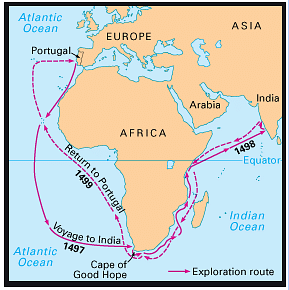

- Vasco Da Gama, led by a Gujarati pilot named Abdul Majid, arrived at Calicut in May 1498. The ruler of Calicut was Zamorin (Samuthiri) in 1498.

- Arab traders had a profitable business on the Malabar Coast, along with participants from India, Arabs, Africans from the east coast, Chinese, and Javanese. They dealt with Pedro Alvarez Cabral for the spice trade.

- After negotiations, the Portuguese established a factory at Calicut in September 1500.

- Vasco da Gama also set up trading factories at Cannanore and Cochin, which became important trade centers for the Portuguese.

- In 1505, the King of Portugal appointed a governor in India for a three-year term and equipped the incumbent with sufficient force to protect the Portuguese interests.

- Francisco De Almeida, the newly appointed governor, was asked to consolidate the Portuguese position in India and destroy Muslim trade by seizing Aden, Ormuz, and Malacca. He was also advised to build fortresses at Anjadiva, Cochin, Cannanore, and Kilwa.

- The real founder of the Portuguese power in the East.

- In East Africa, Portuguese strongholds off the Red Sea, at Ormuz, in Malabar, and at Malacca.

- The principal port of the sultan of Bijapur became the first bit of Portuguese territory in India.

- Nino da Cunha assumed the governor of Portuguese interests in India in November 1529 and almost one year later shifted the headquarters of the Portuguese government in India from Cochin to Goa.

- Bahadur Shah of Gujarat, during his conflict with the Mughal emperor Humayun, secured help from the Portuguese by ceding to them in 1534 the island of Bassein with its dependencies and revenues. He also promised them a base in Diu.

- However, Bahadur Shah’s relations with the Portuguese became sour when Humayun withdrew from Gujarat in 1536. Favorable Conditions for Portuguese.

- Favorable Conditions for Portuguese

(i) Gujarat, ruled by the powerful Mahmud Begarha (1458-1511).

(ii) The Portuguese had cannons placed on their ships.

- Sixty miles of coast around Goa, The Portuguese established military posts and settlements on the east coast at San Thome (in Chennai) and Nagapattinam (in Tamil Nadu)

- Treaties were signed between Goa and the Deccan Sultans in 1570.

- The Portuguese always had a role to play in successive battles for the balance of power between Vijayanagara and the Deccan sultans, between the Deccan and the Mughals, and between the Mughals and the Marathas.

- The Vedor da Fazenda is responsible for revenues and the cargos and dispatch of fleets.

- Intolerant toward the Muslims

- Zeal to promote Christianity

- In 1608, Captain William Hawkins with his ship Hector reached Surat. Jahangir appointed him as a mansabdar of 400 at a salary of Rs 30,000.

- In November 1612, the English ship Dragon under Captain Best and a little ship, the Osiander successfully fought a Portuguese fleet.

- Based on an imperial Farman circa 1579, the Portuguese had settled down on a riverbank which was a short distance from Satgaon in Bengal and later migrated to Hooghly.

- On June 24, 1632 - Hooghly was seized. Bengal governor becomes Qasim Khan.

- The emergence of powerful dynasties in Egypt, Persia, and North India and the rise of the turbulent Marathas as their immediate neighbors.

- The union of the two kingdoms of Spain and Portugal in 1580-81, dragging the smaller kingdom into Spain's wars with England and Holland, badly affected India's Portuguese monopoly of trade.

- The religious policies of the Portuguese gave rise to political fears and, Dishonest trade practices.

- They earned notoriety as sea pirates.

- Goa which remained with the Portuguese had lost its importance as a port after the Vijayanagara empire's fall.

- Marathas invaded Goa-1683.

- Rise of Dutch and English commercial ambitions.

- Diversion to the west due to the discovery of Brazil.

[Intext Question]

- Marked the emergence of naval power.

- Portuguese ships carried cannons.

- The Portuguese onshore's significant military contribution was the system of drilling groups of infantry, on the Spanish model, introduced in 1630.

- Masters of improved techniques at sea.

Cornelis de Houtman was the first Dutchman to reach Sumatra and Bantam in 1596. Cornelis de Houtman

Cornelis de Houtman

Dutch Settlements

- The Dutch founded their first factory in Masulipatnam (in Andhra) in 1605.

- Captured Nagapatam near Madras (Chennai) from the Portuguese and made it their main stronghold in South India.

- The Dutch established factories on the Coromandel coast, in Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, and Bihar.

- In 1609, they opened a factory in Pulicat, north of Madras. Their other principal factories in India were at Surat (1616), Bimlipatam (1641), Karaikal (1645), Chinsura (1653), Baranagar, Kasimbazar (near Murshidabad), Balasore, Patna, Nagapatami 1658), and Cochin (1663).

- They carried indigo manufactured in the Yamuna Valley and Central India, textiles and silk from Bengal, Gujarat, and the Coromandel, saltpeter from Bihar, and opium and rice from the Ganga Valley.

Anglo-Dutch Rivalry

- This posed a severe challenge to the commercial interests of the Dutch by the English.

- The climax of the enmity between the Dutch and the English in the East was reached at Amboyna (a place in present-day Indonesia, which the Dutch had captured from the Portuguese in 1605) where they massacred ten Englishmen and nine Japanese in 1623.

- 1667- Dutch retired from India and moved to Indonesia.

- They monopolized the trade in black pepper and spices. The most important Indian commodities the Dutch traded were silk, cotton, indigo, rice, and opium.

- The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 AD facilitated the restoration of Dutch Coromandel and Dutch Bengal to Dutch rule, but they were returned to British rule as a result of the clause and provisions of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 AD.

- This required the Dutch to ensure all property and establishment transfers until March 1, 1825 AD.

- As a result, by the middle of 1825 AD, the Dutch had lost all of their commercial sites in India.

- The obvious happened as a result of the compromise. In 1667 AD, all parties reached an agreement in which the British committed to withdrawing fully from Indonesia in exchange for the Dutch withdrawing from India to trade in Indonesia, based on a give-and-take formula.

The decline of the Dutch in India

- The Dutch got drawn into the trade of the Malay Archipelago.

- Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-74), links between Surat and the new English town of Bombay were disrupted, resulting in the Dutch forces capturing three homebound English ships in the Bay of Bengal.

- The English retaliation resulted in the defeat of the Dutch, in the battle of Hooghly (November 1759), thereby ending Dutch ambitions in India.

- Their concerns were trade.

- Commercial interest lay in the Spice Islands of Indonesia.

- Battle of bara-1759 the English defeated Dutch.

Charter of Queen Elizabeth I Queen Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth I

- Francis Drake's voyage around the world in 1580 and the English victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588. In 1599 'Merchant Adventurers' formed a company.

- On December 31, 1600, Queen Elizabeth I issued a charter with exclusive trading rights to the company named the 'Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies'.

Foothold in West and South

- In 1611, the English started trading at Masulipatnam on the southeastern coast of India and later established a factory in 1616.

- Establish a factory at Surat under Thomas Aldworth-1613.

- In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe came as an accredited ambassador of James I to Jahangir's court.

- Secure permission to set up Agra, Ahmedabad, and Broach factories.

- Bombay had been gifted to King Charles II by the King of Portugal as a dowry when Charles married the Portuguese princess Catherine in 1662. Bombay was given over to the East India Company on an annual payment of ten pounds only in 1668.

- Bombay was made the headquarters by shifting the Western Presidency's seat from Surat to Bombay in 1687.

- 'Golden Farman' was issued by the Sultan of Golconda in 1632. On payment of 500 pagodas a year, they earned the privilege of trading freely in the ports of Golconda.

- The British merchant Francis Day, in 1639 received from the ruler of Chandragiri permission to build a fortified factory at Madras which later became Fort St. George and replaced Masulipatnam as the headquarters of the English settlements in south India.

- English extended their trading activities to the east and started factories at Hariharpur in the Mahanadi delta and Balasore (in Odisha) in 1633.

Foothold in Bengal

- Shah Shuja, the subahdar of Bengal in 1651, allowed the English to trade in Bengal in return for an annual payment of Rs 3,000.

- Factories in Bengal were started at Hooghly (1651) and other places like Kasimbazar, Patna, and Rajmahal.

- William Hedges, the first agent and governor of the Company in Bengal, and Shaista Khan, the Mughal governor of Bengal in August 1682.

- The English retaliated by capturing the imperial forts at Thana (modern Garden Reach), raiding Hijli in east Midnapur, and storming the Mughal fortifications at Balasore.

- On February 10, 1691, the English factory was established the day an imperial Farman was issued permitting the English to "continue contentedly their trade-in Bengal" on payment of Rs 3000 a year instead of all dues.

- In 1698, the English succeeded in getting permission to buy the zamindari of the three villages of Sutanuti, Gobindapur, and Kalikata (Kalighat) on payment of Rs 1,200.

- The fortified settlement was named Fort William in the year 1700 when it also became the seat of the eastern presidency (Calcutta) with Sir Charles Eyre as its first president.

Farrukhsiyar’s Farmans

- In 1715, an English mission led by John Surman to the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar secured three famous farms, giving the Company many valuable privileges in Bengal, Gujarat, and Hyderabad. The farmans thus obtained were regarded as the Magna Carta of the Company. Their important terms were:

(i) Company’s Exports and imports are exempted from customs duties except for the annual payment of 3000 rupees in Bengal.

(ii) Issues of data (passes) for transportation.

(iii) East India Company was exempted from the levy of all duties in surat on an annual payment of 10000.

(iv) The coins of the Company minted at Bombay were to have currency throughout the Mughal empire. - Sir William Norris was its ambassador to the court of Aurangzeb (January 1701-April 1702).

- Under pressure from the Crown and the Parliament, the two companies were amalgamated in 1708 under the title of 'United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies.

Foundation of French Centres in India

- Louis XIV, the king’s famous minister Colbert, laid the Compagnie des Indes Orientals (French East India Company) in 1664 the Compagnie des Indes Orientals was granted a 50-year monopoly.

- In 1667, Francois Caron headed an expedition to India, setting up a factory in Surat. Mercara, a Persian who accompanied Caron.

- Founded another French factory in Masulipatnam in 1669, In 1673 established a township at Chandernagore near Calcutta.

Pondicherry Nerve Centre of French Power in India

- In 1673, Sher Khan Lodi, the governor of Valikondapuram (under the Bijapur Sultan) granted Francois Martin, the Masulipatnam factory director.

- Pondicherry was founded in 1674. And Caron became the French governor.

- Mahe, Karaikal, Balasore, and Qasim Bazar were a few important trading centers of the French East India Company.

Early Setbacks to the French East India Company

- The Dutch captured Pondicherry in 1693.

- The Treaty of Ryswick concluded in September 1697 and restored Pondicherry to the French, the Dutch garrison held on to it for two more years.

- Francois Martin died on December 31, 1706.

- In 1720, the French company was reorganized as the 'Perpetual Company of the Indies’.

The Anglo-French Struggle for Supremacy: the Carnatic Wars First Carnatic War (1740-48) First Carnatic War

First Carnatic War

- Background - Carnatic-Coromandel coast and its hinterland, Extension of the Anglo-French War caused by the Austrian War of Succession.

- Immediate cause - France retaliated by seizing Madras in 1746, Thus beginning the First Carnatic War.

- The result - The treaty of Aix-La Chapelle was signed bringing the Austrian War of Succession to a conclusion.- Madras was handed back to the English. The French got their territories in North America.

- Significance - The First Carnatic War is remembered for the Battle of St. Thome (in Madras) on the banks of the River Adyar fought between the French forces and the forces of Anwar-ud-din, the Nawab of Carnatic, to whom the English appealed for help.

Second Carnatic War (1749-54)

- The background for the Second Carnatic War was provided by rivalry in India.

- Cause -

(i) The opportunity was provided by the death of Nizam-ul-Mulk, the founder of the independent kingdom of Hyderabad, in 1748, and the release of Chanda Sahib, the son-in-law of Dost Ali, the Nawab of Carnatic, by the Marathas.

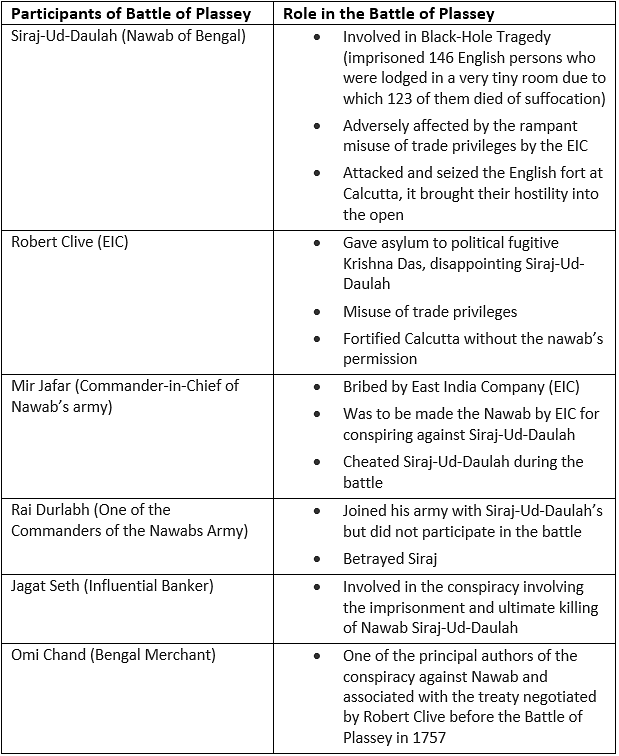

(ii) The French supported Muzaffar Jang and Chanda Sahib's claims in the Deccan and Carnatic, respectively, while the English sided with Nasir Jang and Anwar-ud-din. - During the war

(i) The combined armies of Muzaffar Jang, Chanda Sahib, and the French defeated and killed Anwarud- din at the Battle of Ambur (near Vellore) in 1749.

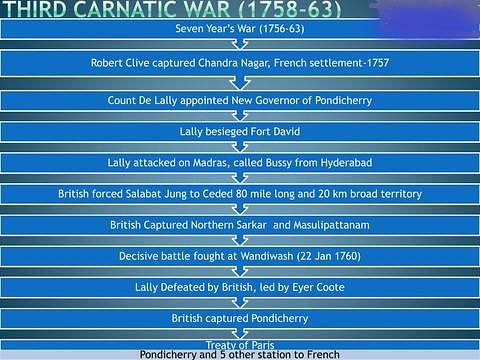

(ii) Muzaffar Jang became the subahdar of Deccan, and Dupleix was appointed governor of all the Mughal territories to the south of the River Krishna.